I gave this book a second shot after dropping it over a year ago. A friend insisted it was an informative read, so I dove back in despite the denseness of the author’s writing. I still found the writing to be strained, and the author struggles with explaining scientific concepts and genomic research fluidly. His writing about history is much more enjoyable to read, but the science is necessary to comprehend the history which made the overall read a tad arduous. The effort is worth it though – I personally learnt a lot about Indian pre-history, the answers that DNA research has now brought to light that didn’t exist even 10 years ago, and how that corroborates or contradicts stories and theories I’ve heard growing up.

On Writings and Maps

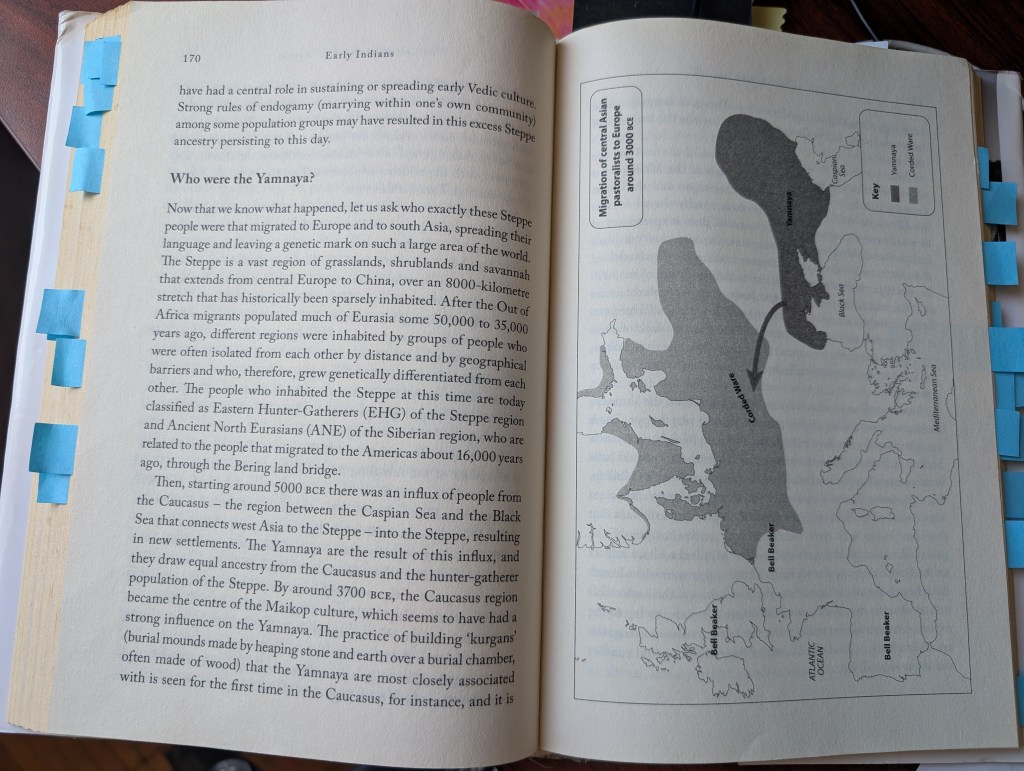

My other overall gripe with this book is the poor use of imagery and maps. They exist, yes, but they were undoubtedly added as an after-thought. Perhaps the editor thought the sub-200 paged book would ‘not cut it’ and added padding with some maps and illustrations. Whatever the reason, the book could have benefitted from illustrations that were more relevant, and better placed with the narratives.

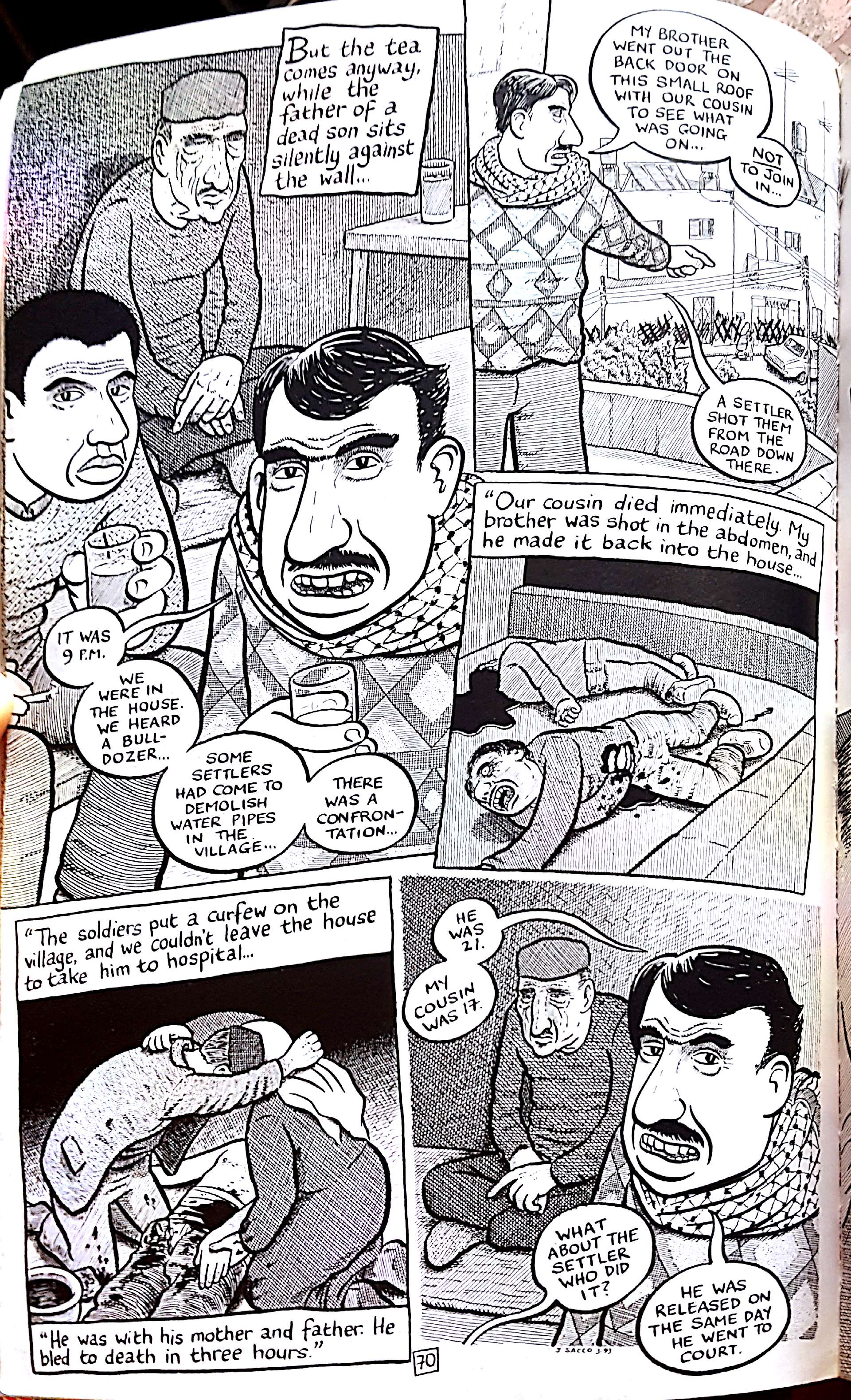

Example below depicts my annoyance: the page on the left is incomplete, with a half-sentence hanging off that would need the reader to flip past the map to complete the author’s train of thought. In doing so, oops, you’ve now skipped the map that would have helped understand the geography of what the author is speaking about, so you need to go back.

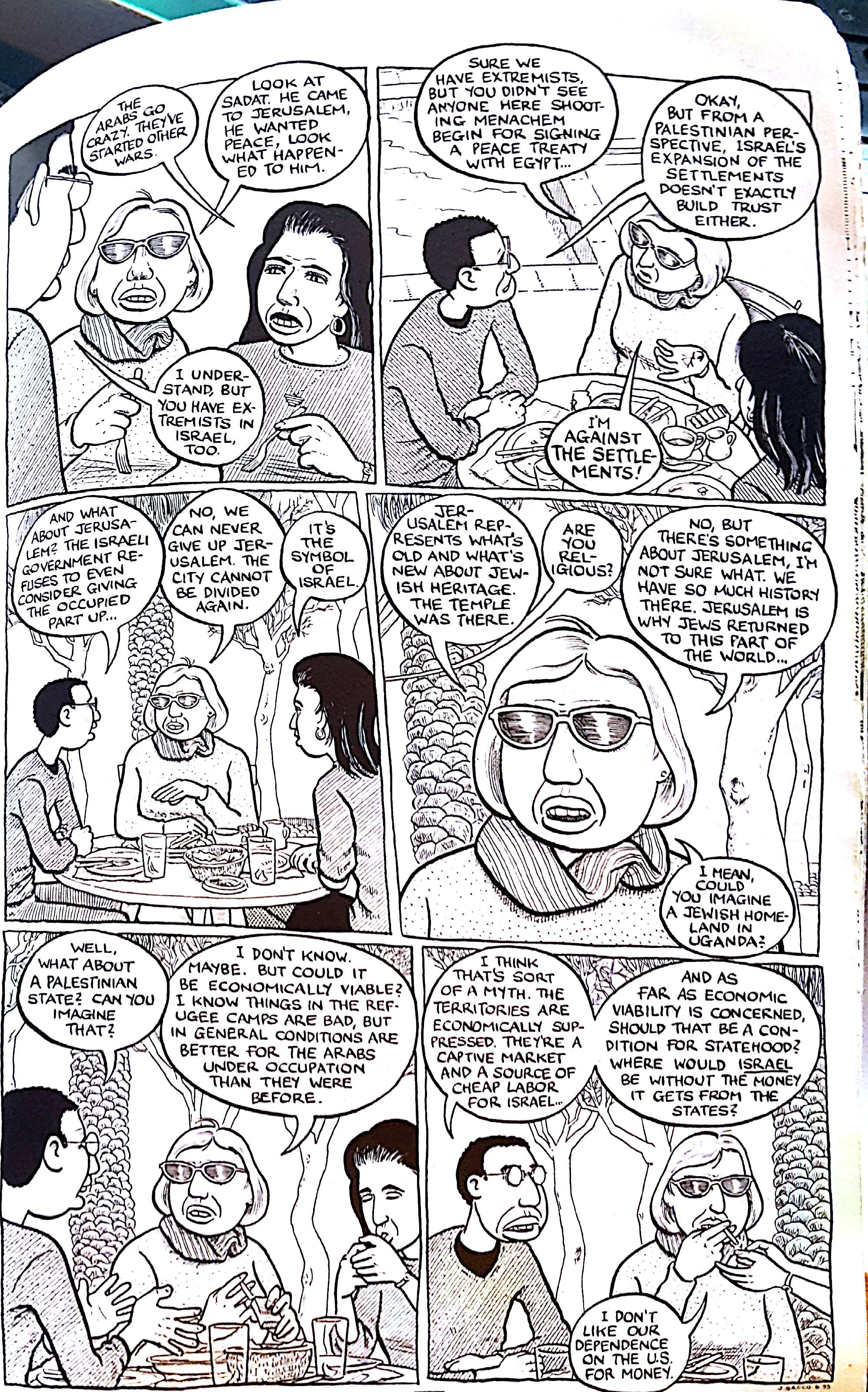

Sometimes, the images are irrelevant to the current topics of dense, scientific explanations – this left me infuriated a couple of times. Here is a page from early in the book where the author sets out to explain some pretty complicated genomic science, how mtDNA and Y-chromosomes are passed along generations, and how they have been helpful in our current understanding of history alongside archeological evidence. Alongside this complexity, we get some fairly irrelevant cell diagrams: the connect is ‘biology’, I guess?

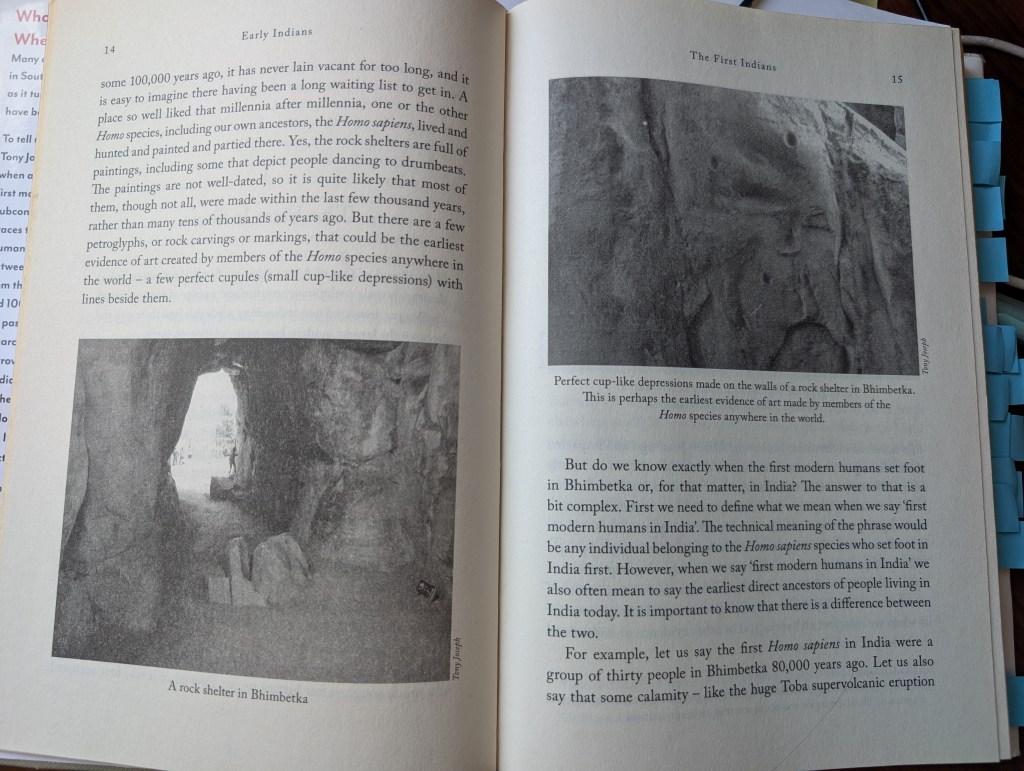

Here’s another page for comparison where I’d argue that the architecture of the prose and imagery were done right! We have the author narrating early Indian evidence and humanity’s first artistic endeavors from the Bhimbetka caves in Madhya Pradesh, and after a crisply ended sentence we see images of both the caves, and the early Homo Sapiens’ art in the photos provided – we just needed more of these, and less of the cases above! Would have made the read a lot more pleasant!

Fascinating Lessons

Alright, gripes about the editing of the book aside, here are some fascinating things I learnt from this read!

- India has not invested enough in the understanding of our early history. The resources provided to archeology seem quite minimal, leaving a lot of unturned places of history. Tony Joseph says that one of the places we should visit to get a sense of the grandeur of the Harappan Civilization would be to visit Dholavira in the Great Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, a 7 hour drive from Ahmedabad. Dholavira was a crucial hub for the Harappan Civilization’s overseas trade with Mesopotamia!

- Unicorns were a part of Proto-Indian history too! The commonest seal in the Harappan Civilization, about 60% of all discovered seals have the image of a unicorn. So much so that it is believed to have been a ‘state symbol’ similar in importance to the Ashoka Chakra today. (Did anyone else think Unicorns were a western fascination?)

- Reconstructed Proto-Dravidian vocabulary helps identify the timing of when Proto-Zagrosian and Proto-Dravidian languages (and hence people) separated: not before animals like goat and sheep were domesticated, or early forms of agriculture, but not after writing was invented. ‘Tal’ which means to push in Proto-Dravidian, means to ‘write’ in Elamite (language spoken in Elam, in present day Iran). McAlpin explains that the original meaning of ‘Tal’ was to ‘push in’, and since early cuneiform writing involved clay tablets with the same action, the word went on to take the second meaning of ‘writing’ in Elamite after writing was invented. Proto-Dravidians must have separated from Elamites before writing was invented, and therefore the word never acquired this meaning! The word for writing in Dravidian languages instead derives from ‘drawing’ or ‘paint’.

- The worship of the phallic symbol could have been as old as the Harappan Civilization. After Indo-European language speakers reached South Asia, the language of the Harappans became limited to South India, while the culture and myths melded with those of the new Indo-Aryan-language-speaking migrants to create what we now perceive as the core of Indian culture.

- Those who brought Dravidian languages to south India (around 2800-2600 BCE) must have been pastoralists.

- One of the ways scientists determined where Dravidians had lived was by analyzing the names of towns and cities at different points in history: a name that ended in ‘palli’ or ‘halli’ would have been derived from Dravidian languages, and would help point to the latest stage at which the population used a Dravidian language for daily interaction.

- Languages spoken by Indians today fall into four major families. That I hadn’t learnt this before stunned me.

- Dravidian: A fifth of Indians (including me!) speak a Dravidian language which has no language-kin outside of South Asia

- Indo-European, is spoken by over 75% of Indians today and is spread all the way from South Asia to Europe

- Austroasiatic: spoken by just 1.2% of the population in India and is spread across South Asia and East Asia

- The short explanation for the presence of Austroasiatic language in India is that it arrived from South-East Asia around 2000 BCE as a part of the farming migrations in China. Based on the sub-species of rice harvested in India and in China, science has also shown that rice farming was not brought to India from China.

- These fall within one of two families of languages: Munda, or Khasi. Both these are related to Mon-Khmer languages of Vietnam, Cambodia, and parts of Nepal, Burma, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Thailand, Laos and southern China. Nicobarese is also an Austroasiatic language.

- Munda is spoken in eastern India, particularly Jharkhand, and in central India in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra

- Khasi is spoken in Meghalaya and to some extent in Assam

- Tibeto-Burman: spoken by under 1% of Indians and is spread across South Asia, China, and South-East Asia

- The Yamnaya, a civilization from Kazakh (and a part of the Steppe Herder lineage) burst upon Europe around 3000 BCE, a thousand years before their descendants reached South Asia. The new influx into Europe by these migrants were identified using their Corded Wares, a distinctive style of pottery.

- Yamnayas were a male centric population. A small number of males must have been wildly successful in spreading their genes, based on genomic evidence. Local pre-existing Y chromosomes get wiped out dramatically after the invasion by Yamnayas.

- Basque is the only indigenous non-European language left in Western Europe today (derived from pre-Steppe migrations)

- These migrants from Steppe had a clear preference for a non-urban, mobile lifestyle which could be part of the reason why India had to wait for over a millennium after the Harappan Civilization for its second urbanization.

- On the Vedas:

- Indian culture is not synonymous with Vedic culture: Harappan civilization precedes the earliest vedas, and hence also the earliest instance of the caste system

- Rigveda denounces ‘Shishna-Deva’ or phallic-worshippers, while the Harappans leave no doubt that phallus worship was a part of their faith. In fact, archeologists have found clear evidence of the deliberate destruction of phallic idols and symbols in Dholavira and other sites.

- There is no horse-related imagery in Harappan culture, and an abundance of it in the Rig-Vedas

- Rigveda has a word for Copper ‘ayas’, since later when Iron was discovered, the word ‘krsna ayas’ was used to describe it – settling the timeline for the vedas to have been written somewhere between 2000 BCE and 1400 BCE: meaning the earliest veda post-dates the Harappan Civilization.

- Caste System materialized out of nowhere, literally. It did not come with the Aryan migration (or the Steppe/Yamnayas), nor was it created at the same time as the Rig Vedas. In fact, DNA evidence shows that even until 100 CE, the populations in the sub-continent were mixing with each other. Around 100 CE however, genetic evidence shows that the inter-mixing stopped: as though a new ideology imposed on the society new restrictions and a new way of life. “It was social engineering on a scale never attempted before or after, and it succeeded wildly, going by the results of genetic research”. The 4 varnas are mentioned in the part of the Rig Veda most likely believed to have been written later, and the oldest veda also makes no mention of occupational roles for these varnas.

- Genetics and Food Habits: Consumption patterns for dairy in India point to a clear demarcation that northern and western parts of India consume more milk and milk products than southern and eastern Indians. They also consume less meat and fish than their southern and eastern counterparts. It’s been shown that a specific mutation 13910T which originated in Europe 7500 years ago is responsible for allowing humans to digest milk beyond infancy. (Fun fact: Humans are the only species to have known to develop this mutation and be able to digest milk past infancy. All the cartoons we see of an adult Tom drinking milk is a lie, and milk for adult cats is mildly poisonous to their lactose intolerant selves. Kittens can drink milk, just as all human babies can digest milk.) This mutation is of particular interest here since a countrywide screening of DNA samples shows that lactase tolerance reduces as we move from North-West India to South-East.

Overall, this was a fascinating read that I’d recommend, one that is worth the wrestling with some dense pages.