Faroe Islands: Not spelt Farrow, but can be spelt Faeroe instead. The official language is Faroese. They’ve been inhabited since the 4th century, and settled/ruled/owned by Norwegians, English, Danes, Icelandic. If we were to enforce a narrowly won referendum from 1946, Faroe Islands would be an independent state, but that was annulled by the King of Denmark, and so the islands belong to (surprise, surprise!) the Danish Kingdom. Sorry, where is this archipelago, you ask? Midway between Iceland, Norway and the UK in the Atlantic Ocean.

Christmas Island: Closer to Indonesia than to Australia which governs the land, Christmas Island hovers just about 350 km south of the Java Islands. It was named so because of its discovery on Christmas Day in 1643 by an English sea captain with an allegiance to the East India Company. The British lost the island to the Japanese during World War II but eventually reclaimed it. And later, the British Colony of Singapore sold Christmas Island to Australia for $20 Million in 1946 for its Phosphate mines. English, Malay, Mandarin, Cantonese, and Hokkien are the primary spoken languages, and the island boasts of a population of under 2000 people. Christmas Island is known for a natural world’s phenomenon as well, but more on that later.

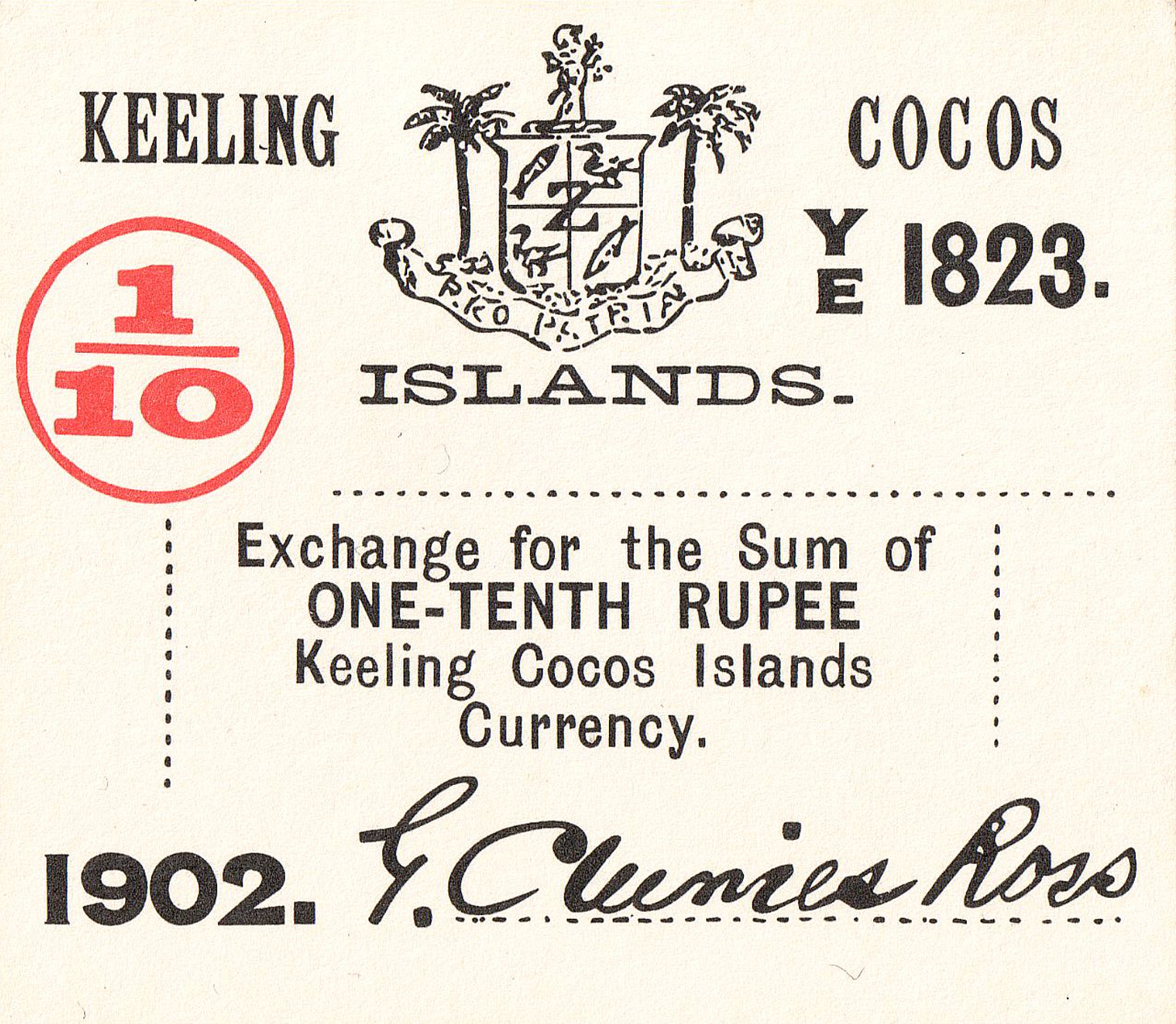

Cocos (Keeling) Islands: I’m cheating a little bit by picking this next, since it shares most of its history with Christmas Island. Further south of Indonesia (and still nowhere close to Australia), Cocos Islands were also purchased by Australia from the British Singapore in 1955. The island was discovered by William Keeling in 1605, but not inhabited until a certain John Clunies-Ross stopped by 200 years later, planted the flag of the Union Jack, and left with the notion of bringing his wife and family to settle in these islands. Before he could do that though, another wealthy Englishman Alexandre Hare, had the same idea. Except, instead of bringing his family, Hare brought in Malay women to create a ‘voluntary’ harem and settled in the islands. When John Clunies-Ross arrived with his family and some soldiers, a feud grew between the two Brits, with John ultimately winning the islands from a distraught Alexandre whose ‘wives’ had run away or left him for the newly-landed soldiers. John then took over administration of the islands, and even minted his own currency, the Cocos Rupee.

The Brits officially controlled the islands from 1906, even though all the land belonged to John. These islands have a fascinating history in both the world wars, owing to a telegraph station the Brits built here, on an island that they helpfully called ‘Direction Island’. Today, the islanders (all 600 of them) predominantly practice Sunni Islam, and speak Malay. The islands are named so after their abundance of coconut trees.

Related, and absolutely fascinating: The annual red crab migration of Christmas Island occurs around October/November each year, and sees an estimated 40 million red crabs coolly walking, climbing and shimmying across the island to get to the ocean in order to breed. The male crabs start earlier, leaving their homes in the jungle to reach areas around the ocean where they create burrows and wait for their potential female mates. The females arrive fashionably late, and spend an additional couple of weeks incubating the eggs and making a further trip to the ocean to finally release the larvae into the water. Whales migrate to the coast of Christmas Island to feast on the newly released larvae. The baby crabs that survive all this then make the treacherous journey back to the jungles in the middle of the island. Here’s a video of all this chaos.

Things I learnt from this video:

- There are crab infrastructures created in Christmas Island each year: this includes crab bridges, detours, and underpasses.

- Crabs are cannibals. They feed on the ones that don’t make it to the ocean.

- Crabs can climb over absolutely anything.

- A female red crab can release up-to 100,000 eggs at once.

- Christmas Islanders are alarmingly calm about red crabs.

Here’s a bonus article featuring a video by David Attenborough on the same migration.